SF author Kit Reed told Tor.com that her latest novel, Enclave, started as many of her novels do: with a dream.

“I dream in color, it’s always a movie and sometimes I’m in it, as myself,” Reed said in an interview. “This was one of those times. I was in a Gothic building turned into a boarding school and I was a kid in front of a frozen computer and there was something terribly urgent about it. The computer—the entire school system—had been crippled by a virus and I had to fix it or… Somehow I knew that elsewhere in this sprawling building dozens of kids were terribly sick, and if I couldn’t fix the computer in front of me, they were all going to die.”

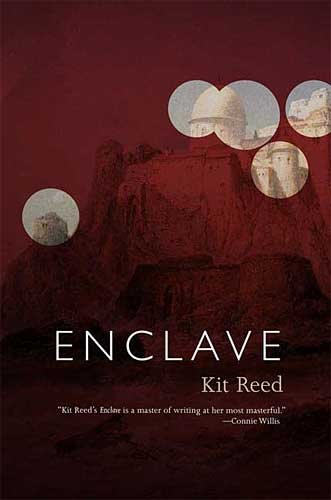

Enclave is a story about Sarge, an idealistic ex-Marine who thinks he can solve the world’s problems by fixing the minds and hearts of their young. “He brings a boatload of rakehell rich kids to remote Mount Clothos, where he’s turned an abandoned Benedictine monastery into the Academy,” Reed said. “The military does things by the numbers. He thinks he and his staff of misfits can reform the kids.”

It seems to be going well until MMORPG gamers Killer Stade and the Prince accidentally crash the Academy server. “At the exact same time that a mysterious stranger surfaces in the old chapel, and the kids start getting desperately sick,” Reed said.

Sarge is determined to atone for certain things he did in the service and save his kids in some of the same ways the Marine Corps saved him. “But he’s [just] one of five central figures,” Reed said. “The others are 12-year-old Killer, who’s at school because he accidentally killed a guy; Cassie, the hard-pressed physician’s assistant who came because she’s in love with Sarge; Brother Benedictus, the last monk left after the old abbot died, and the injured intruder; not even Benny, knows who he is.

Reed says that everything she writes is a challenge because she has to “piss and sweat and struggle” until she gets it right. “This one had a lot of moving parts and the particular challenge was turning a fragment of a dream into something real, which meant figuring out who everybody was and what went where and making it all work,” she said.

Reed has some experience living in situations like the kids in the story. “I’ve lived on a military base and in a convent boarding school with dobermans at the bottom of front stairs to keep us in and intruders out, and in college I spent some time at the Naval Academy, where everything was run by the numbers,” Reed said. “I realized that both the military and religious orders depend on discipline to shape people—which routine does, in a lot of ways.”